Wednesday, August 13, 2025

Forte da Capoeira

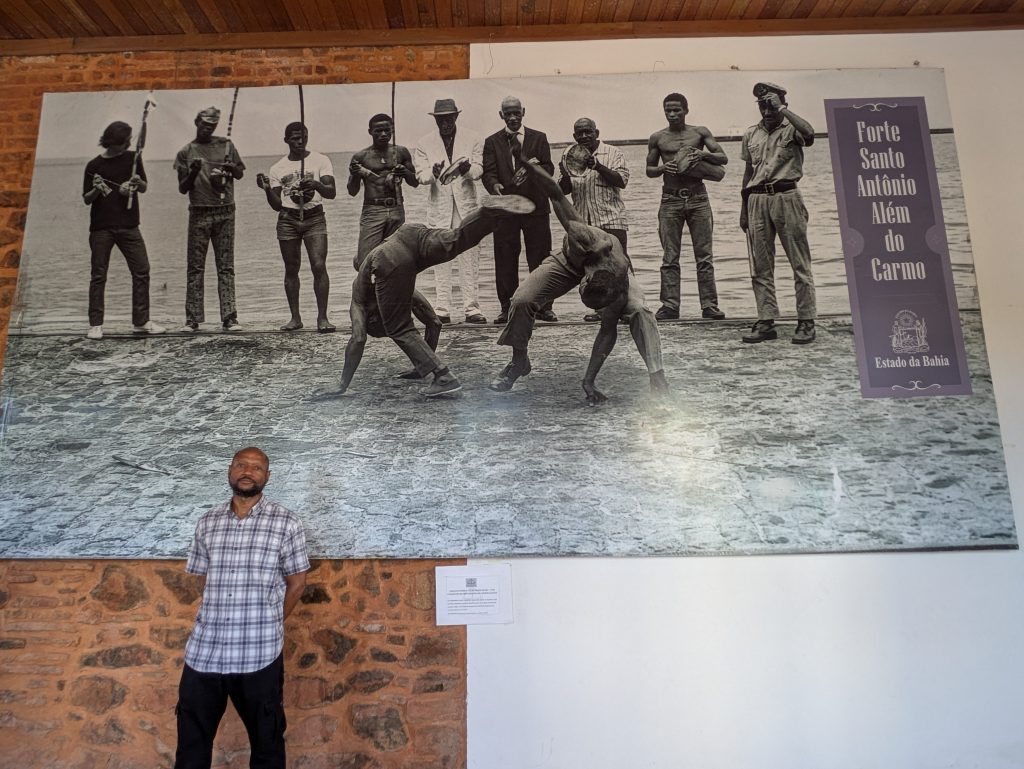

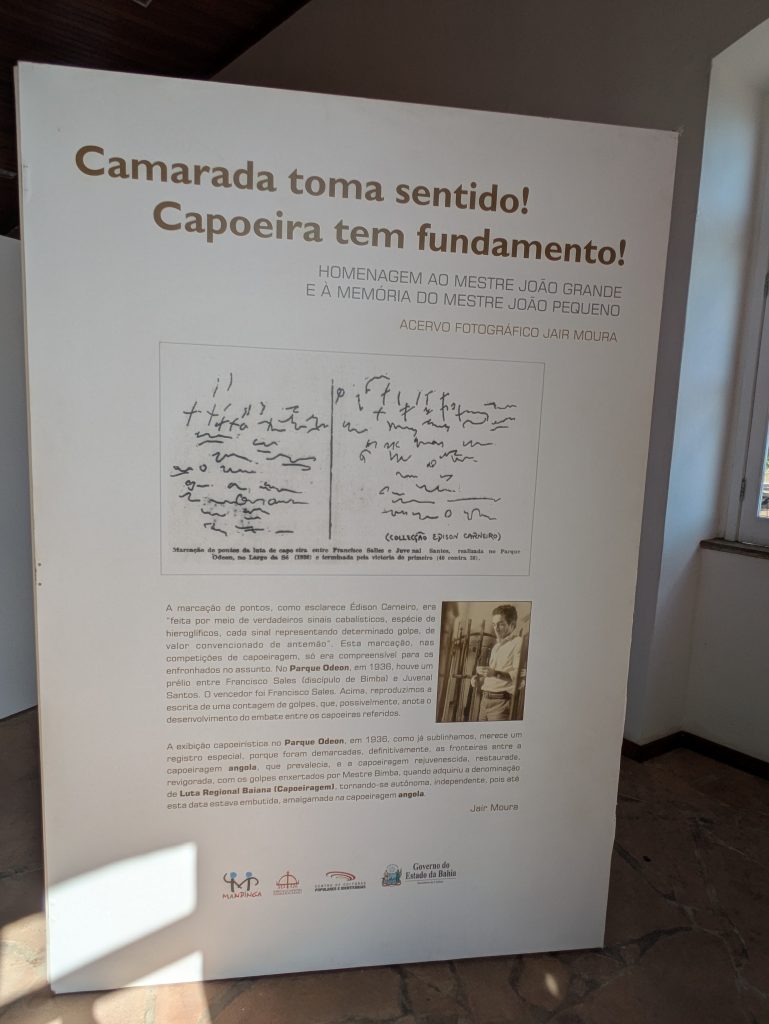

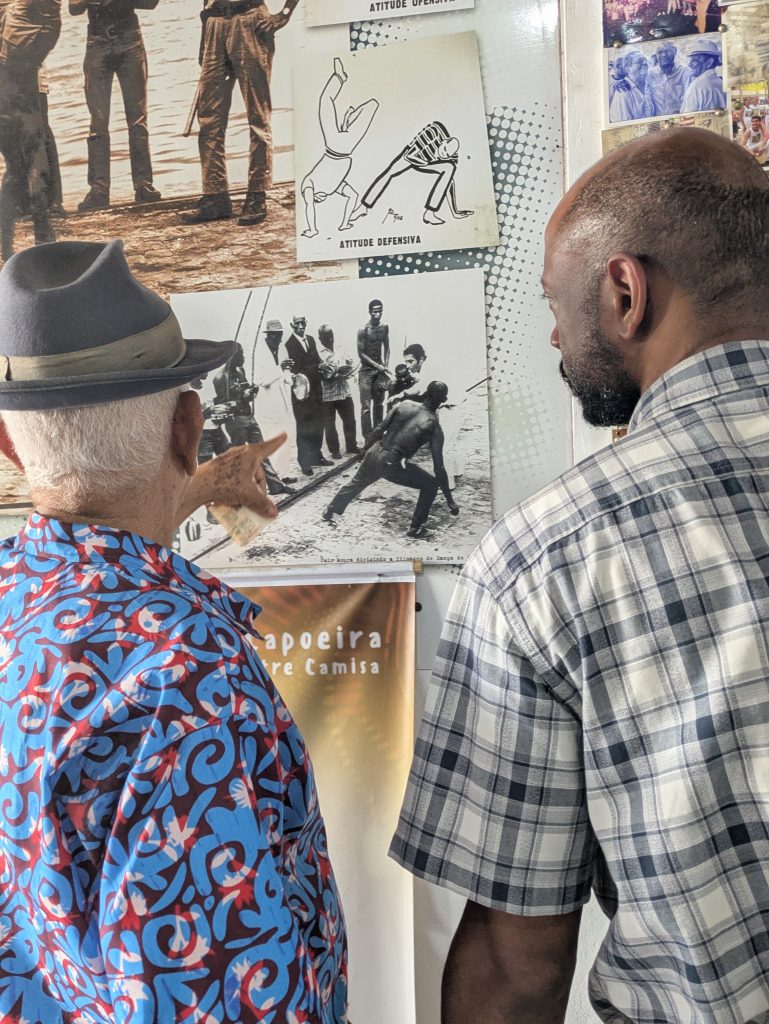

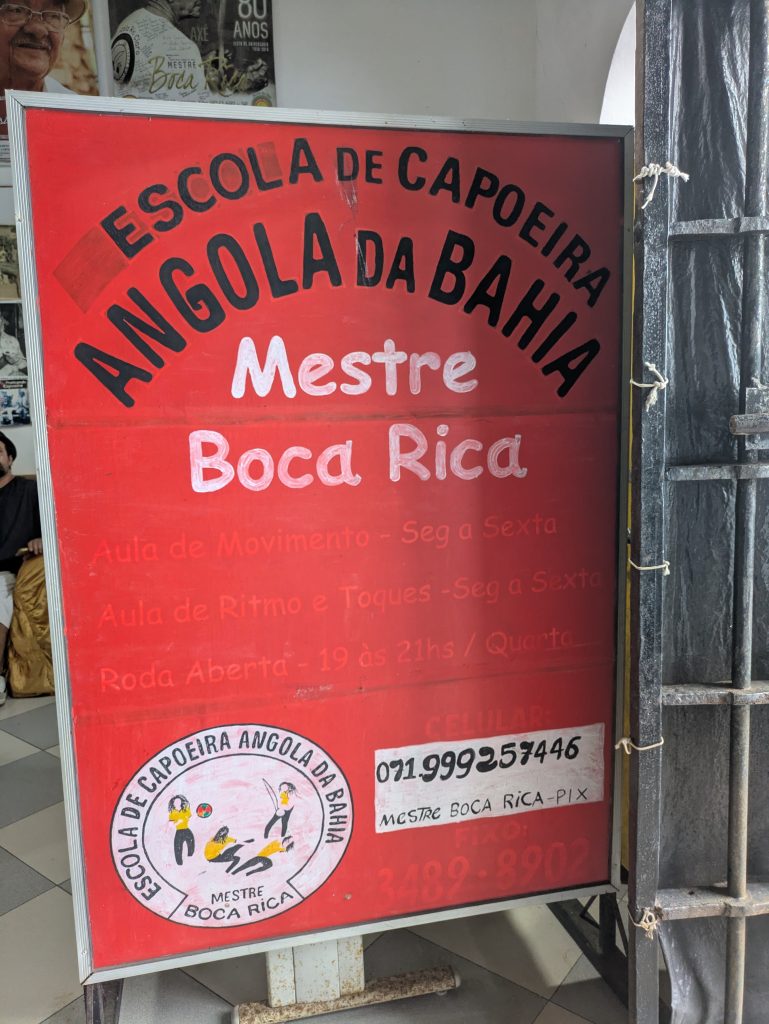

On Wednesday, our final day in Salvador, we returned to the Forte da Capoeira for a private lesson with Mestre Boca Rica. As before, he shared with me stories about his accomplishments as a mestre. He also welcomed several visitors who were visiting the fort.

He and I spent about an hour working on music. We started with the berimbau, then moved to the pandeiro, and finally to the atabaque. He taught me several variations of familiar toques (rhythms) on the berimbau (Toque de Angola and São Bento Grande). He also shared some insights about the version of the toque Cavalaria that was taught by Mestre Pastinha, in addition to its social and historical context.

On the pandeiro, he showed me a way of manipulating the head of it to produce a dynamic, vibratory sound. He also showed me some interesting and beautiful Samba rhythms on the pandeiro. We ended with the atabaque, where again, he gave me some insights on how to improve my playing.

I expressed my sincere thanks to Mestre Boca Rica. His willingness to share his knowledge, his openness, and kindness truly inspired me.

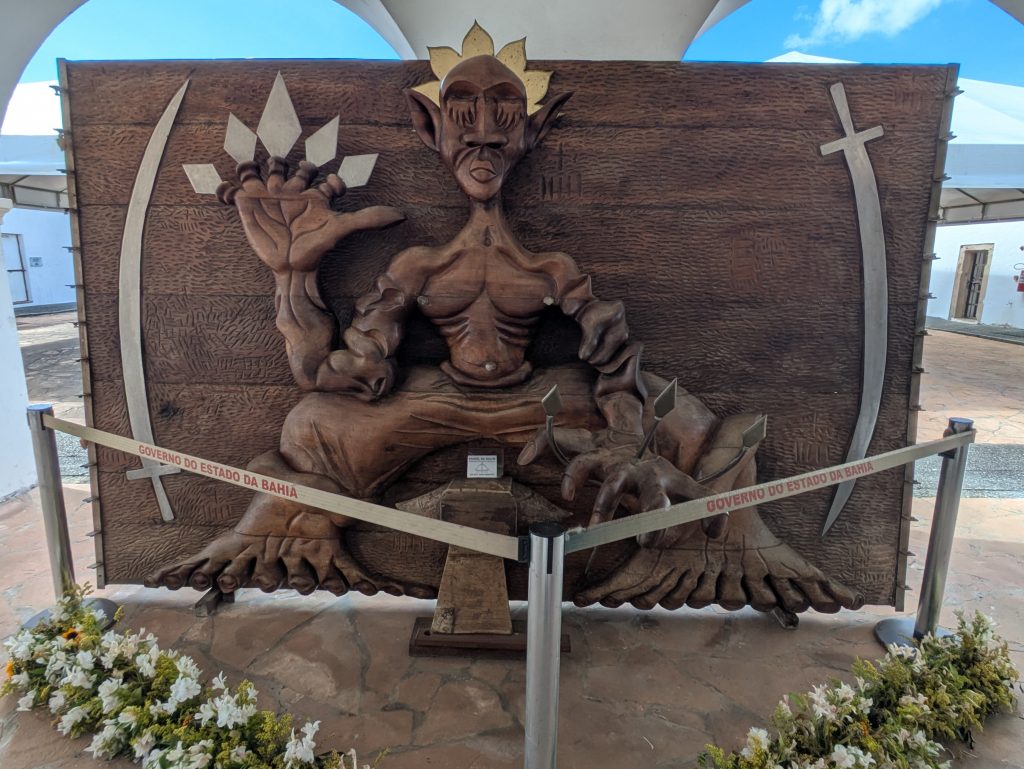

As we prepared to leave the fort, it started to rain. The delay gave me time to remember the Ogun shrine, whereupon I went and left an offering of several coins.

Espaço Cultural da Barroquinha: Exposição fixa Orixás da Bahia

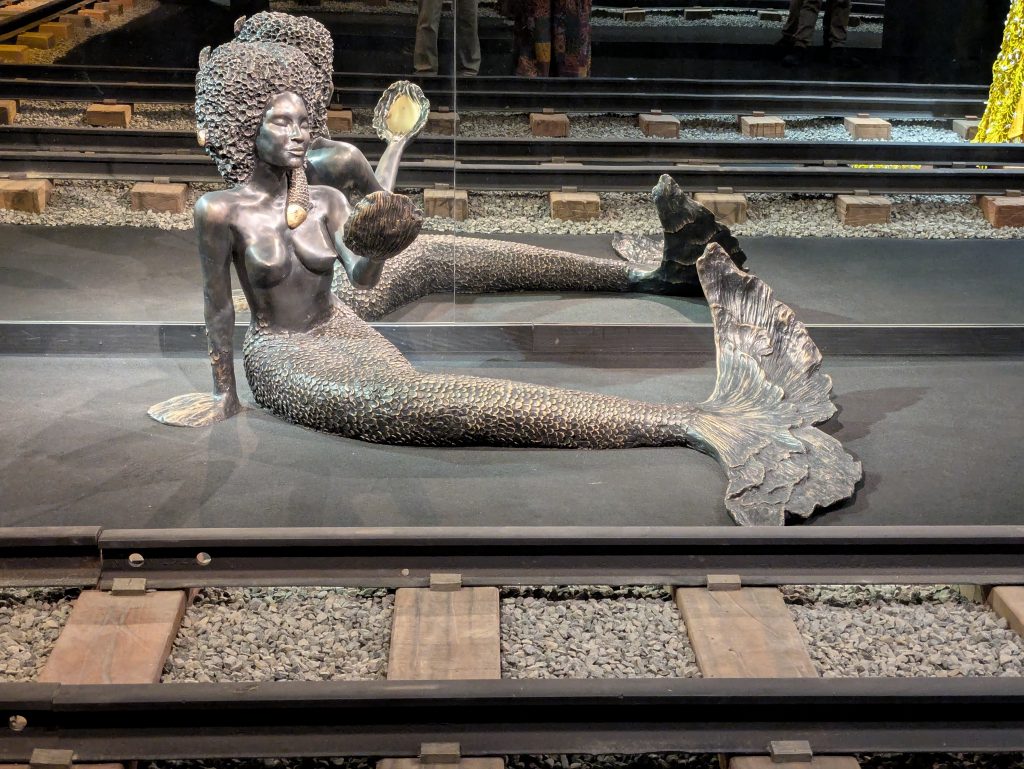

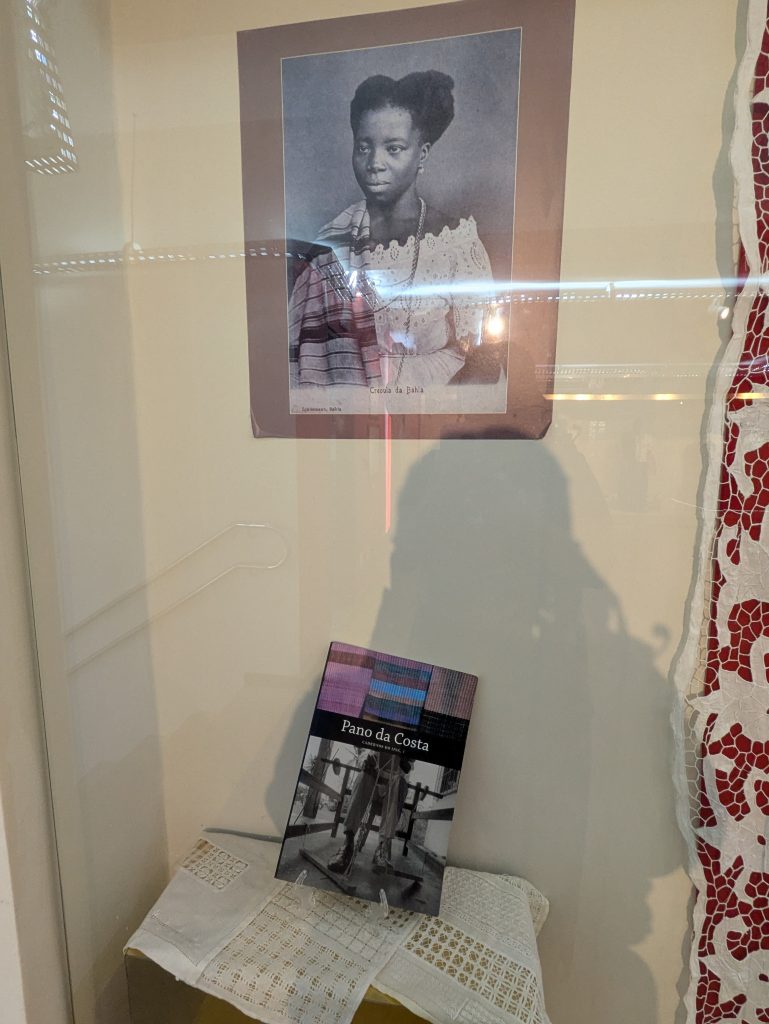

Our last museum-going experience was to the Espaço Cultural da Barroquinha, which featured an exhibition titled, “Exposição fixa Orixás da Bahia.” This exhibit featured statues of various orishas and other objects central to Candomble which were created by the sculptor Alecy Azevedo. The statues were built on the scale of a normal person, adorned in the regalia befitting them, and placed in naturalistic poses. Consequently, each exuded a certain presence that was very discernible. Further, the organization of the space featured two rows of Orixas, one on each side of the narrow chamber with Oxala seated at the far end of the room. This arrangement made the exhibit feel all the more immersive.

Outdoors, just outside of the facility was a shrine to Oxum. It featured a fountain with a representation of Oxum placed above it. Oxum’s colors were displayed, contributing to the calm yet vibrant atmosphere of the setting.

It was a wonderful space and a visually striking homage to this powerful and venerable tradition.

Overall this trip was profoundly moving. It provided so many rich insights into various aspects of Afro-Brazilian history and culture. Salvador is a truly magical place, a city that exudes the beautiful spirit of Africa and its people.