Dique do Tororó

On Monday, we visited three locations–a central theme of the first two was the Orixa tradition in Brazil.

The first trip was to the Dique do Tororó features statues of various Orixas including Iansã, Nanã, Ogum, Oxalá, Oxossi, Oxum, Xangô, Iemanjá; in addition to, Ewá, Logun-Edé, Ossain, Oxumaré. This lake was a very inspiring site as it represents the inscription of African knowledges on the spatial environment. This was a constant element of being in Salvador–the seemingly ubiquitous visual representations of Africanness, especially as exemplified by the Orixas.

Further, given that they represent divine forces, elements of nature, social archetypes, and ethical values and practices–the various representations of the Orixas serve as a potent reminder of how people conceive of and celebrate the sacred in their day-to-day lives. Further, they illustrate how African spirituality functions as an anchor of personal and collective identity, as well as how the concepts and values that the Orixa exemplify possess enduring relevance and meaning in the lives of millions of people both in Brazil and around the world.

Museu Afro-Brasileiro-UFBA

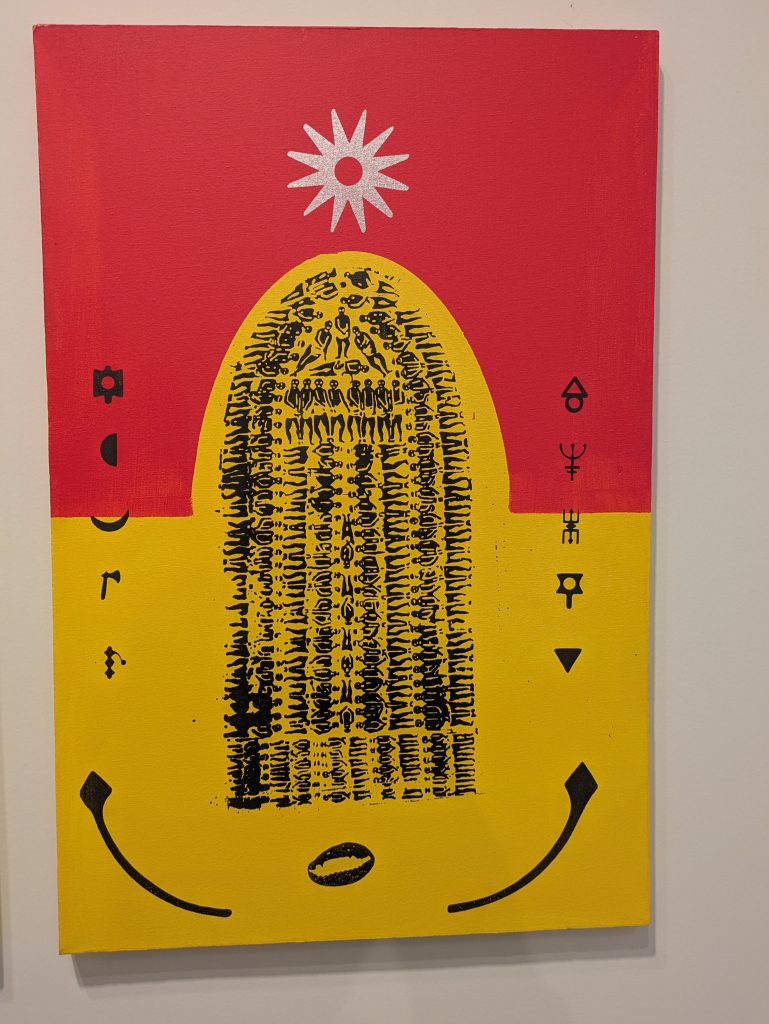

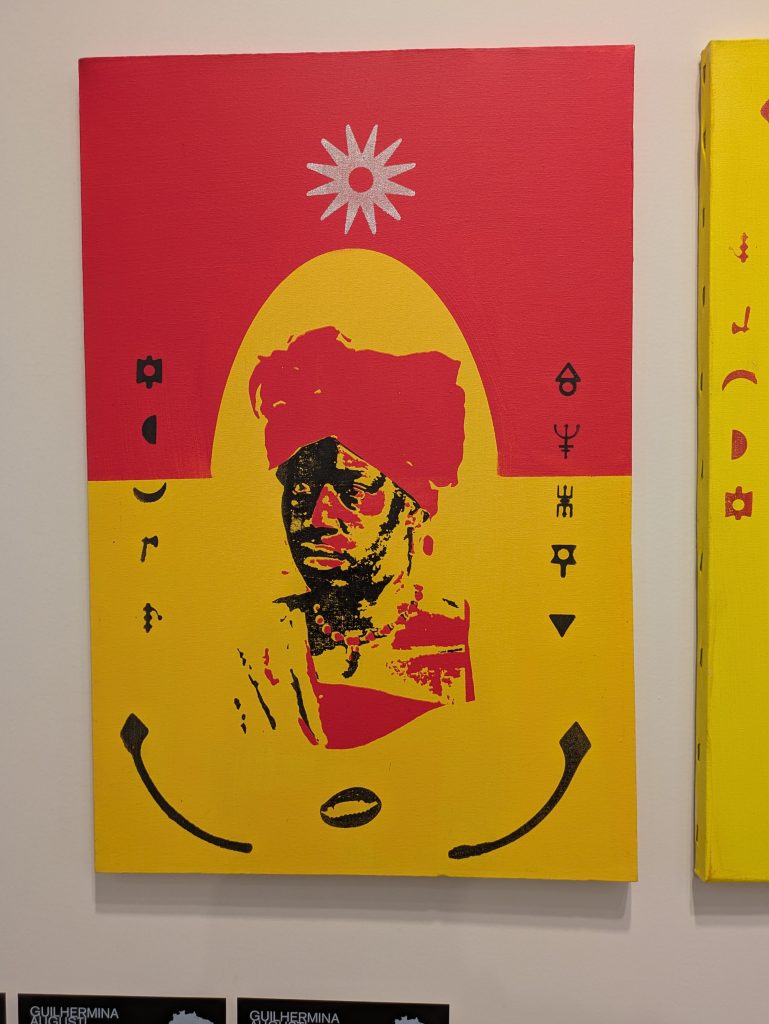

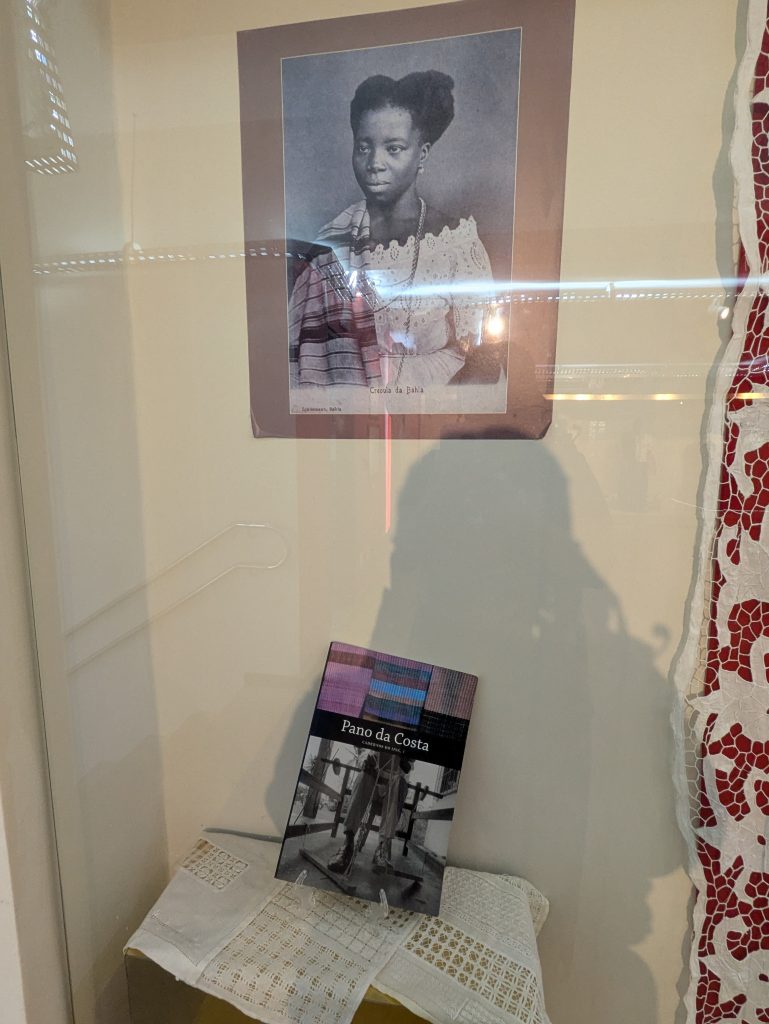

Our second trip was to the Afro-Brazilian Museum contained exhibits on Afro-Brazilian spiritual traditions. It included clothes, paraphernalia, furniture, and various objects associated with the rituals and traditions of Candomblé. There were also items present from Nigeria, Benin, Senegal, and other parts of Africa that demonstrated the depth of continuity between Africa and Brazil.

A highlight of this museum was a collection of works by two artists depicting the orixas. One was a collection of carvings by artist Manoel Do Bomfim which, aesthetically, brings to mind art from the Edo Kingdom of Benin. The other collection was a piece titled “Mural dos Orixás” by Carybé (born Julio Paride Bernabó). It featured 27 panels displaying Orixás from both Yoruba (Ioruba) and Ewe-Fon (Jeje) traditions. It was visually striking in its interpolation of materials–wood, metal, shells, and so on. Further, its use of color produced highly evocative pieces that conveyed motion and energy, capturing the profound beauty and complexity of Candomblé.

Associação de Capoeira Angola Navio Negreiro (ACANNE)

That night I ventured out to my first Capoeira class, which was at the Associação de Capoeira Angola Navio Negreiro run by Mestre Renê Bitencourt, a student of Mestre Paulo dos Anjos, who was a student of Mestre Canjiquinha.

Mestre Renê teaches Capoeira Angola as a mindful, ancestral practice. He constantly emphasizes the importance of listening and observing–listeninig to the music and observing the other practitioner with whom one is playing. His emphasis on listening is analogous to something that my teacher, Mestre Preto Velho says, “Stay in time of the motion within the space of the jogo.” In this way, Mestre Renê taught the need to stay focused on what was happening in the jogo, while also reacting accordingly to the other Capoeirista’s actions. In the context of class he also talked about safety and being “calma” (calm) during one’s practice, and I would add, throughout one’s life.

In terms of physicality, Mestre Renê’s class demonstrated that Capoeira Angola is not easier than other styles of Capoeira. While it places less emphasis on acrobatic movement, it is no less demanding in terms of the dexterity, agility, balance, and strength that it requires. Thus, the movements were physically and mentally demanding. Also, like all Angola styles, his was a grounded form of Capoeira wherein we spent most of our time on the floor and a good amount of that time inverted. Further, his approach to teaching emphasized the dynamic and interactive corporeality of Capoeira–the dynamic exchange of movement and intention inherent in the jogo, the game of Capoeira.

Lastly, the energy of the class was phenomenal. In the roda, Mestre Renê demonstrated that Capoeira is about warriorhood–about facing the challenges of life and living head on. Also, the atmosphere of the class, the community which pervaded the group was palpable. This also reflects the point that one enters into the practice of Capoeira via physical movement, but movement should not be perceived as the totality of the art. It is a practice focused on preparing one to experience life itself.