There are some deeply troubled people in our midst who have unfortunately sought healing in the toxic recesses of social media. Healing is a community vocation, Fu-Kiau reminds us of this. However our communities cannot fulfill this role if they are echo chambers that merely reinforces our isolation and deepens our alienation.

Functional communities are those that affirm the dignity of our humanity while acknowledging the reality of our suffering. These communities remind us that healing can be achieved and encourage us not to desperately cling to pain as some sort of anchor. It is true that pain can shape us, but when held too longingly, it can hurt us. It can warp our humanity. In his novel, The Healers, Ayi Kwei Armah writes, “Pain too long absorbed dulls intelligence. Pain endured, channeled for energy, used for conscious work aimed at ending the source of pain, sharpens intelligence.” When we affirm the possibility of healing and loosen our grasp on pain, we open the door to healing’s actualization.

Healing then becomes our embracing the possibility of transcendence, and communities can support this work in numerous and constructive ways. Functional communities can remind us of, again, the dignity of our humanity, and that of those around us. Functional communities can remind us that our historical experience as Africans in America has been one of surviving unrelenting oppression. Healing communities can remind us that such oppression, does, as it is intended to do, warps humanity and engenders dysfunction. Communities remind us that healing is not merely a matter of healing the individual African person, but that it is, again, a community vocation. Critically conscious healing communities remind us that we must heal ourselves by eradicating the basis of our suffering–oppression.

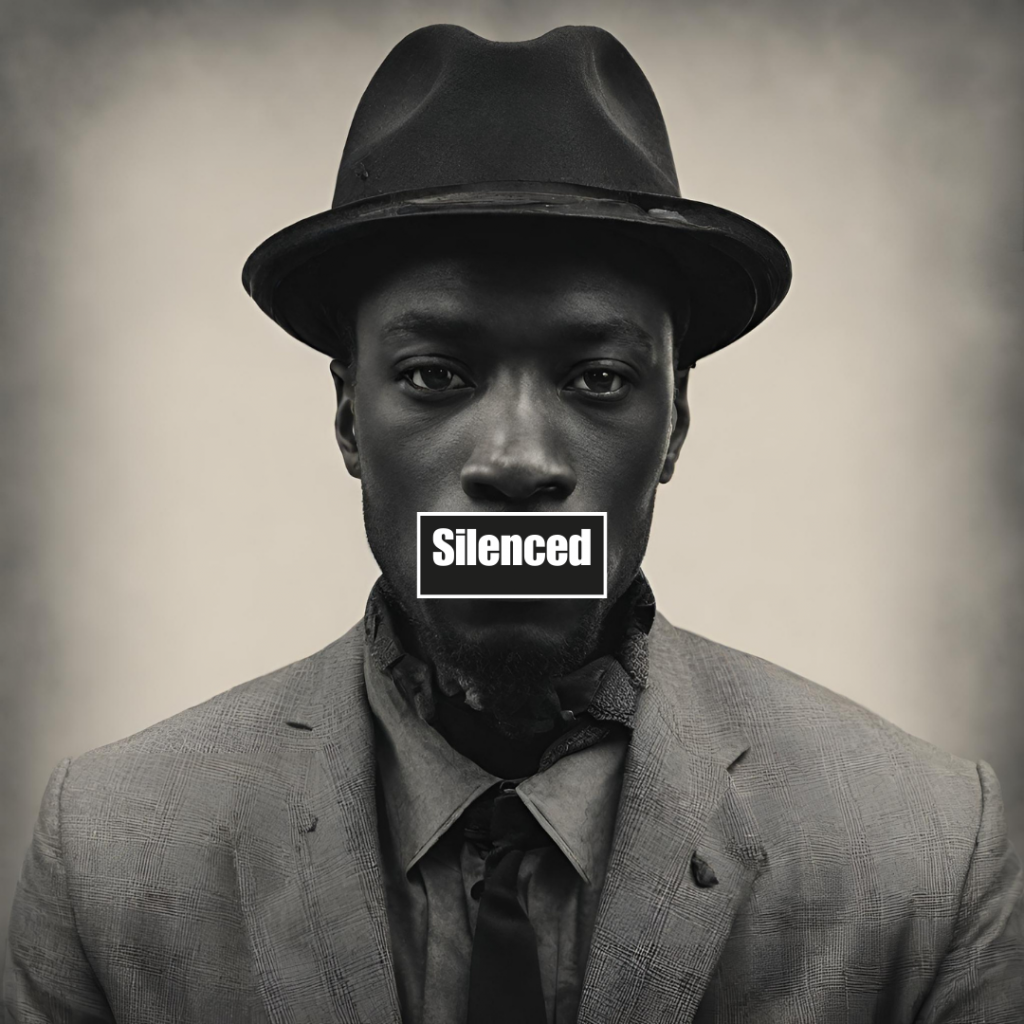

What is meant here by critical consciousness is a degree of discernment which enables one to understand the social and historical factors which have been consequential in shaping the present. Critical consciousness demands that we consider the role of power in shaping society. The power dynamics that have animated our lives and the lives of everyone that we have ever known were firmly established during various stages of conquest and enslavement over the last five centuries. These were historical circumstances that reduced African people to objects of capital, charged with laboring to produce capital. And when that era came to an end, Africans continued to be objects of coercive control subject to debt peonage, voter suppression, containment, rape, and execution in varied forms including lynchings. This era transitioned into one where Africans exist, still as objects of coercive control and racialized containment, and who are socially constructed as a social malignancy–a violent disease, a plague for society, or in the view of some a source of terror within our own communities.

Critical consciousness demands that our analysis always consider the broader constructions of power, and central to this, the production of ideas which seeks to mask its operation in our lives. Thus, a critically conscious person must ask and seek to answer the question of whose interest are served by obscuring the source and causes of dysfunction as it exists in our community? When these sources are masked, we attack one another, rather than the real enemy. A critically conscious must ask how we might effectively address these problems in a manner that eradicates dysfunction by eliminating its structural causes–the system of oppression in which we live, the evolutionary descendant of the system of chattel slavery and colonialism that so malformed our ancestor’s humanity. A critically conscious would recognize that, among other things, we must create the social systems that enables us to be self-determining. That creating the institutions that enable us to feed, clothe, heal, house, educate, and defend ourselves are the most direct and logical response to our continued dependency upon an oppressive system. In fact, the very work of building these systems is the work of restoring community. Ultimately, we must remind ourselves that for all of the dysfunction of our communities, we are ultimately dealing with communities that are the legacy of terror, a legacy that is ever-present. Thus we are not dealing with or residing within self-determining communities, but communities that are, in many respects, the residue of colonialism.

In closing, healing is possible. It begins with us, is augmented by community, and must lead inexorably to reality transformation. For those wishing to journey further down this path Fu-Kiau’s Self-Healing, Power, and Therapy, Armah’s The Healers, and Ani’s Let the Circle Be Unbroken are good resources to consult. Each argues vociferously for the role of African culture and social structures as tools of healing, and within this, for the role of paradigmatic knowledge in healing’s conceptualization and actualization. Angel Kyodo Williams’s Being Black is also beneficial. So too is Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior. These two texts discuss the mind as a site of healing, arguing that our perceptions of reality often exacerbates our suffering. That our own personal quest for greater clarity and awareness, is one that, in fact, augments everything that we do. I would also strongly recommend the deeply insightful Essential Warrior by Shaha Mfundishi Maasi as a potent discourse on healing. He argues that warriorhood and healing are entangled states of being, and that “The purpose of warriorship is to develop an enlightened being who is a human vortex of positive energy, having attained the core of perfect harmony”. He adds that to become a “true warrior one must become ‘nkwa ki moyo’ a vitalist, one who heals the ills of the people.”