Forte da Capoeira

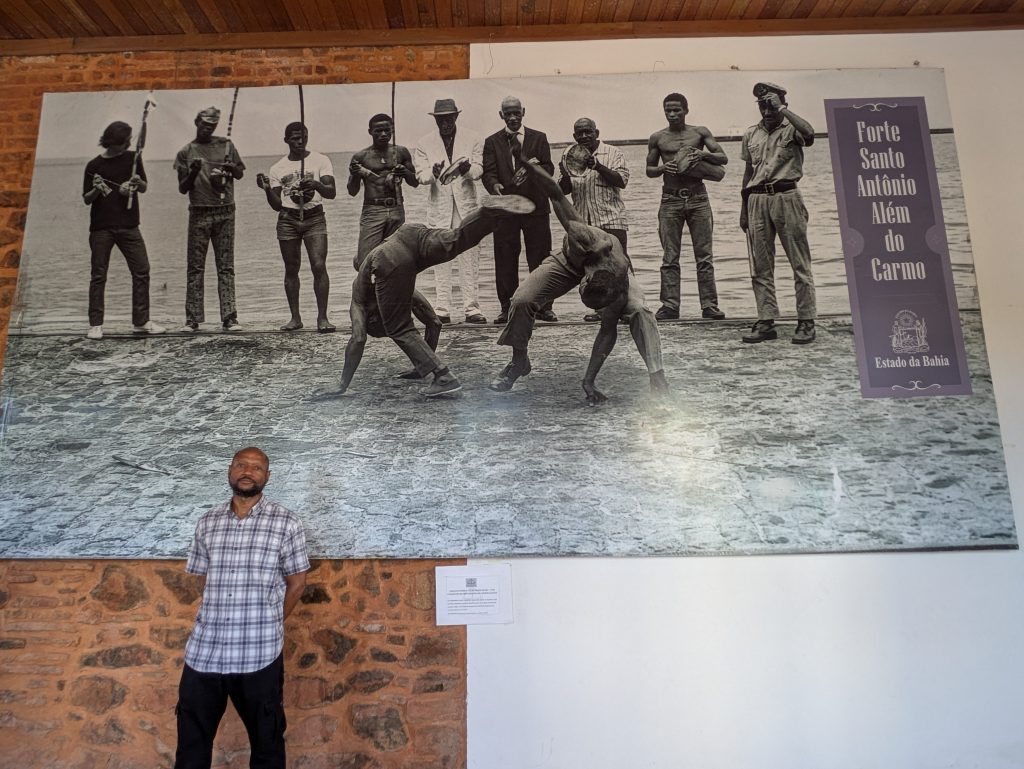

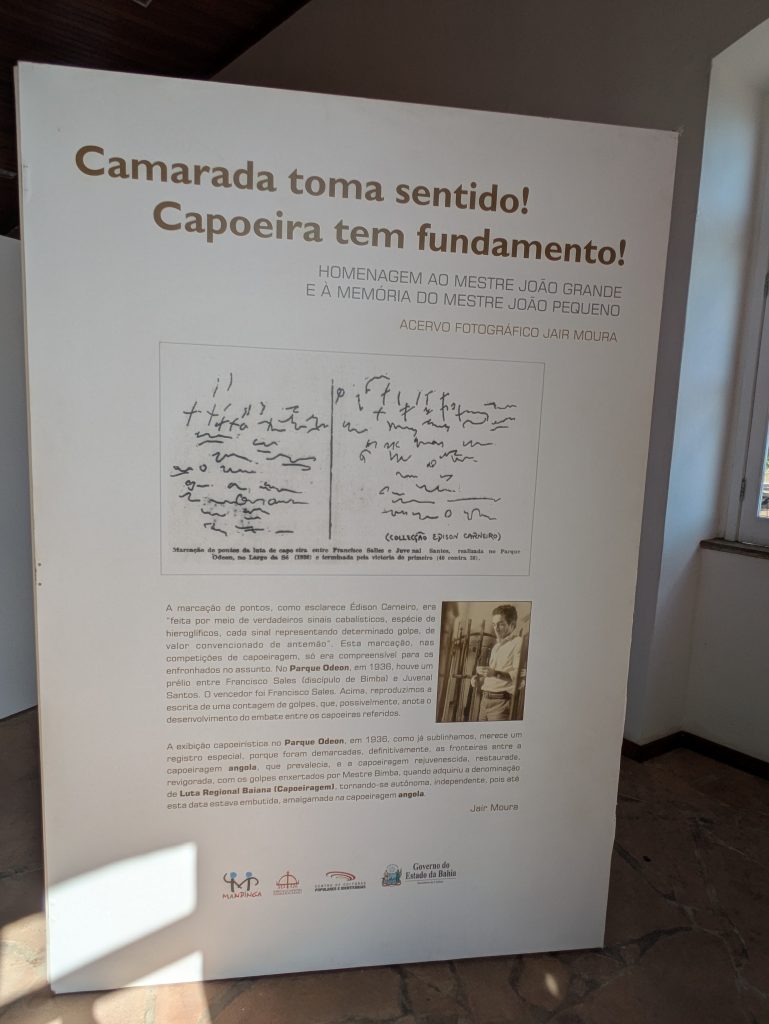

Tuesday’s theme turned out to be Capoeira and began with a visit to the Forte da Capoeira/Forte Santo Antônio.This site is an old fort that has been repurposed into a training space for various Capoeira academies, as well as the location of an exhibit that honors the legacies of Mestres Joao Pequeno and Joao Grande. The exhibit features classic photographs of the two masters playing Capoeira against one another. It also showed several instances of them wielding knives during a certain type of game in Capoeira.

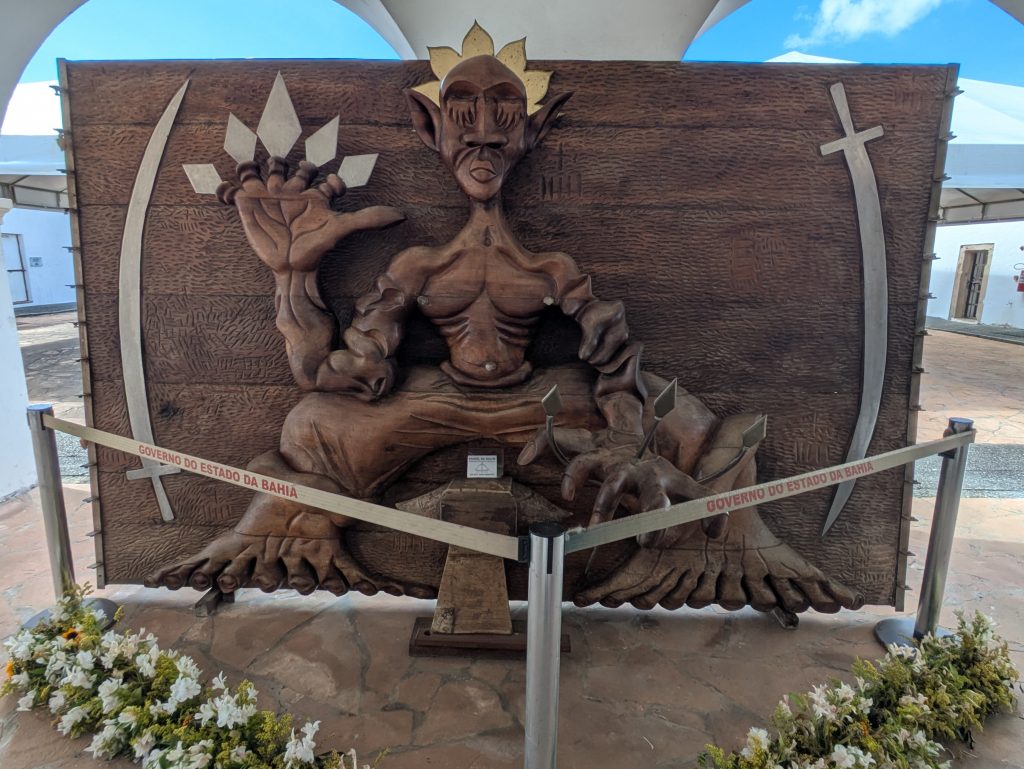

The fort also features a magnificent representation of Ogun that one sees upon entering. Further, it contains a shrine dedicated to him where various visitors left coins as offerings.

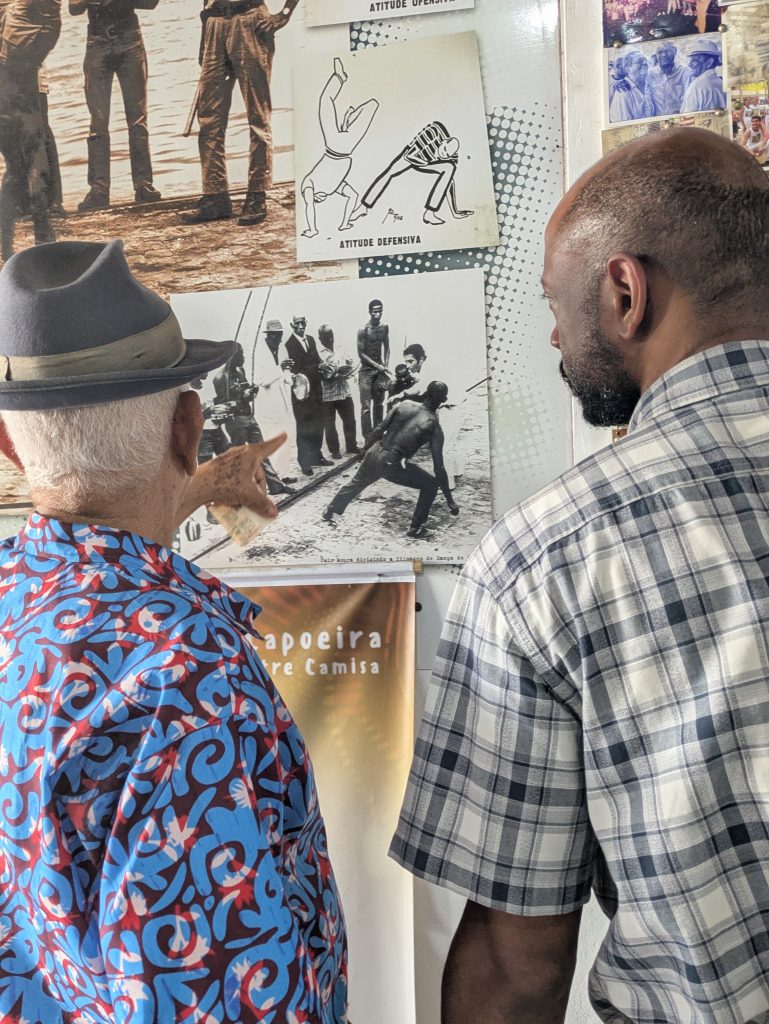

Several mestres had spaces in the forte including Mestres Boca Rica, Bola Sete, Curió, Moraes, and Nenel. While there I visited the academies of Mestres Boca Rica and Mestre Curió (the only two open at the time). Each of these mestres’ academies were like museums. The walls of the Mestre Boca Rica’s academy were covered with posters, articles, awards, pictures, and other symbols of his many years in Capoeira. The walls Mestre Curió’s academy featured various representations of Afro-Brazilian religious traditions, Capoeira, and his decades long presence in the art, in addition to two shrines.

I spent a great deal of time visiting with Mestre Boca Rica, as he shared a great deal with me about his life in Capoeira including his travels, awards, various published works featuring him, and the masters that he’s produced. He took great pride in having produced many masters, considering them as a part of his legacy. He expressed his concern about the distortion of Capoeira’s history–particularly among Capoeiristas in the United States–with people denying its African origins. Further, he expressed his commitment to the maintenance of the art’s tradition and authenticity.

He and I also played some Capoeira music and sang songs together. I was so impressed by his generosity with his knowledge and his skill with the instruments, that I asked if I could return the next day to train with him on the various instruments one-on-one. To which he agreed.

Fundação Mestre Bimba

The final activity of the day was a visit to the academy of Mestre Nenel, son of Mestre Bimba and founder of the Função Mestre Bimba and the group Filhos de Bimba. His academy is located in Pelourinha in a small, but dynamic training space.

I arrived to find Mestre Nenel working on making instruments. I greeted him while I waited for class to start. I was soon joined by over a dozen other visitors, most of whom were from other Capoeira groups in the US, who had also come for class.

Class was taught by two of the mestre’s professors, who, due to the size of the group, divided the class into two groups and taught each group one at a time, with one group taking the floor after another. Their method of teaching was exceedingly efficient and made very effective use of the limited space. The highlight of the class however were the two-person drills, which focused on the application of various takedowns to different types of attacks. Despite my nineteen years in Capoeira, this phase of the class was the most interesting and also challenging. Finally, the class ended with a lively and energetic roda.