On Thursday, August 7, 2025, my wife and I arrived in Salvador, Bahia. I went there to study Afro-Brazilian history and culture generally and to augment my knowledge of Capoeira specifically. While I had been to Brazil prior to this trip, this was my first trip to Bahia and my wife’s first trip to Brazil.

Our agenda was, over the next seven days, to visit several museums and cultural sites. Additionally, I hoped to have the opportunity to visit the academies of several mestres to deepen my knowledge of the movement, music, philosophy, and history of Capoeira.

Friday, August 8, 2025

Casa das Histórias de Salvador

Our first museum excursion in Salvador was to the Casa das Histórias de Salvador to see an exhibit on the Malê Revolt. The museum contained exhibits on the history of Salvador, from colonial times to now. Herein, the history of Afro-Brazilians in shaping the city and its culture were indelible.

One of the highlights of the museum was a film on the Orixá tradition, specifically the various religious festivals that take place in Salvador. This film was colorful and celebratory, highlighting the female orixá and their significance to life and community.

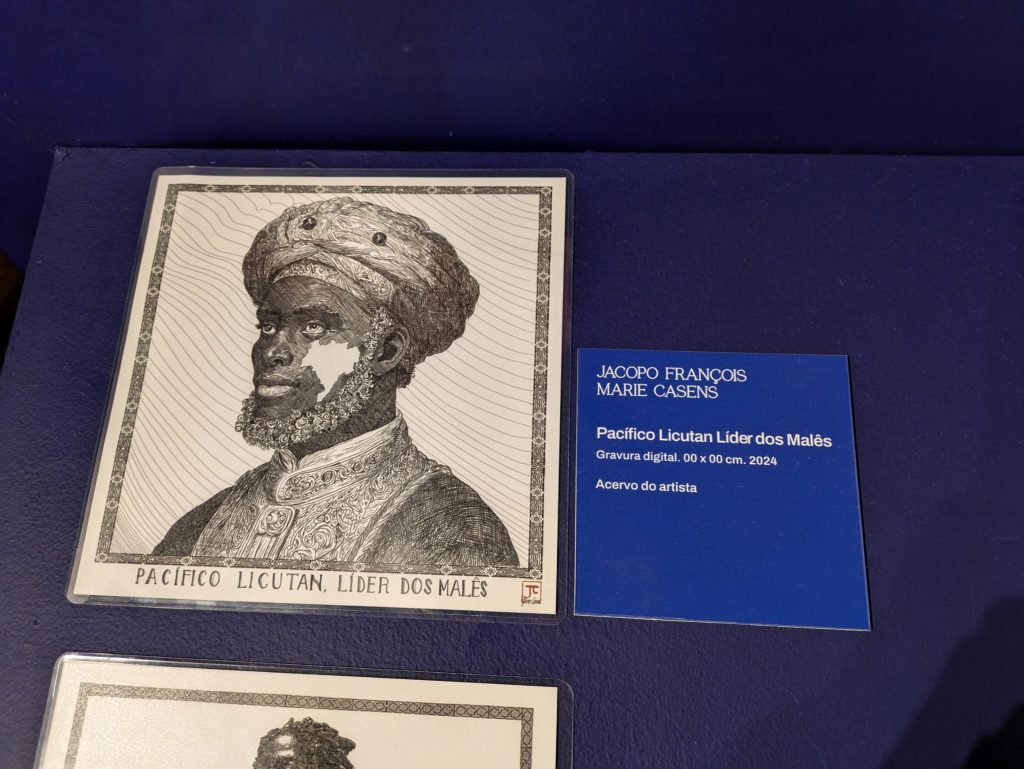

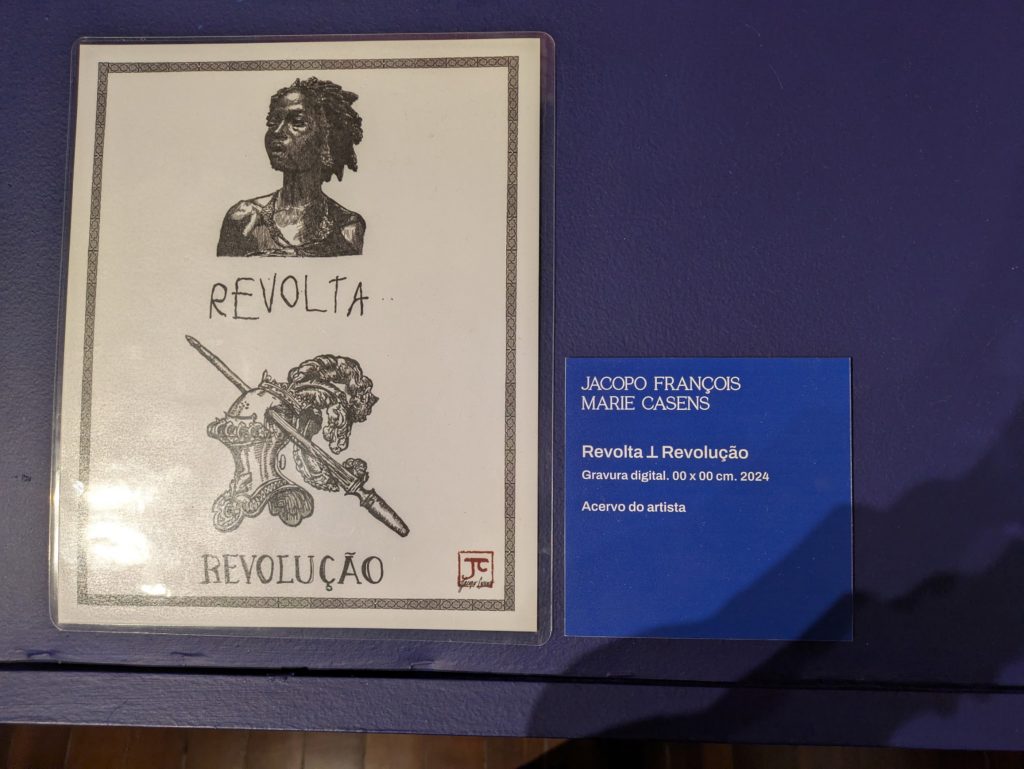

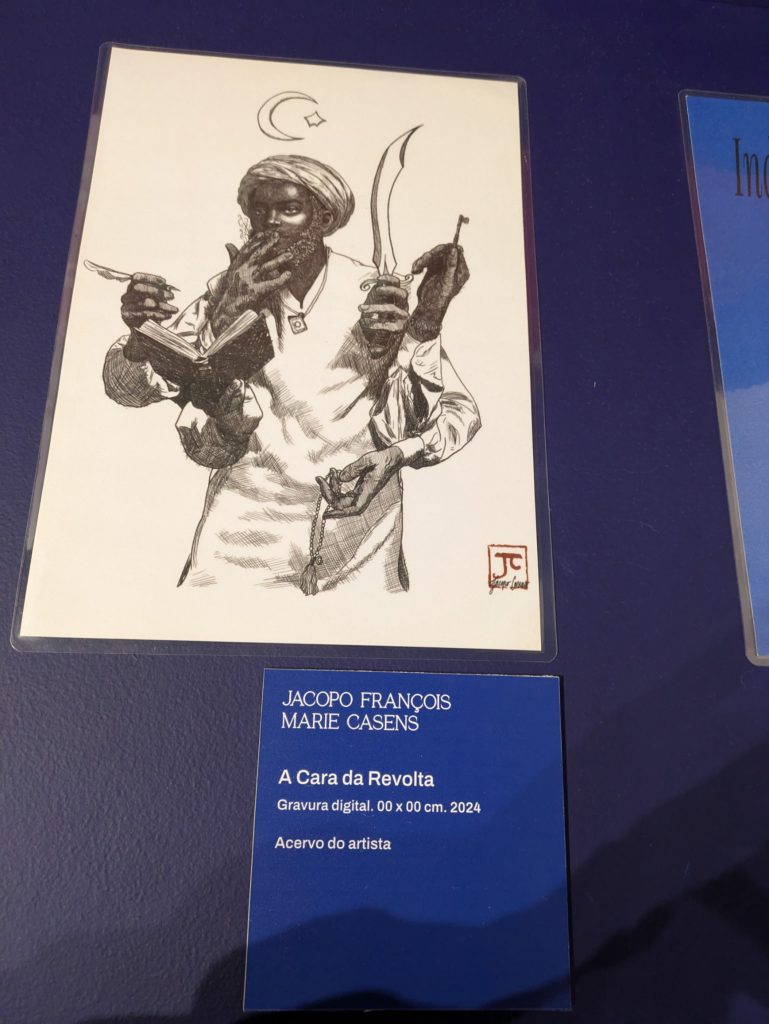

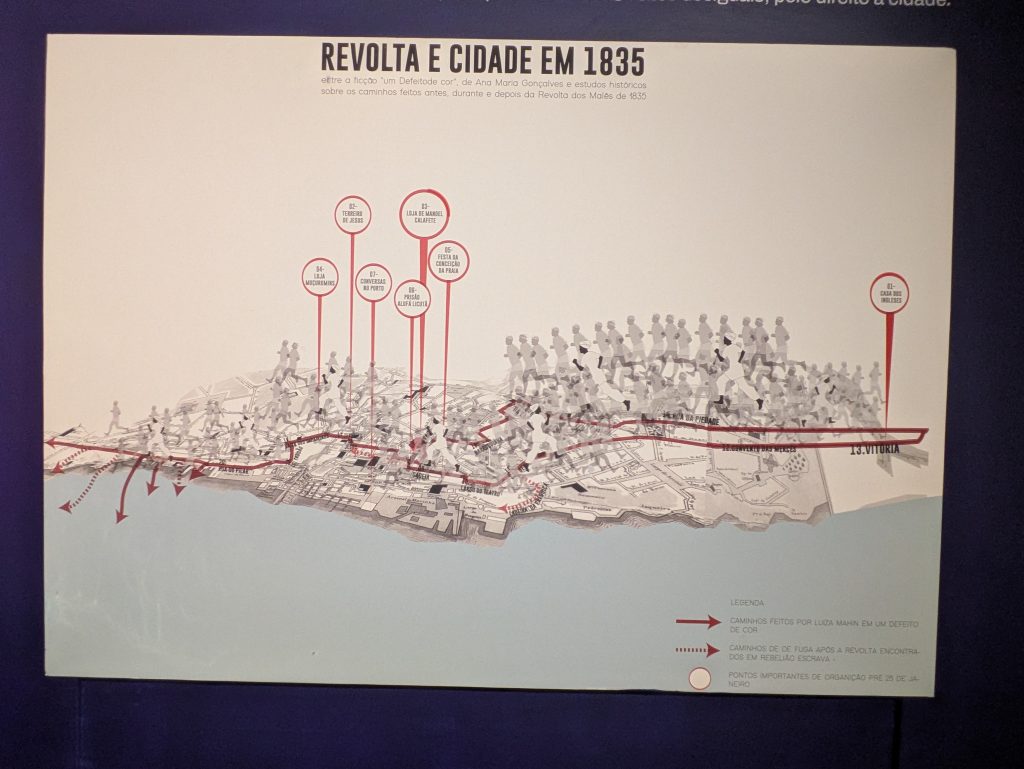

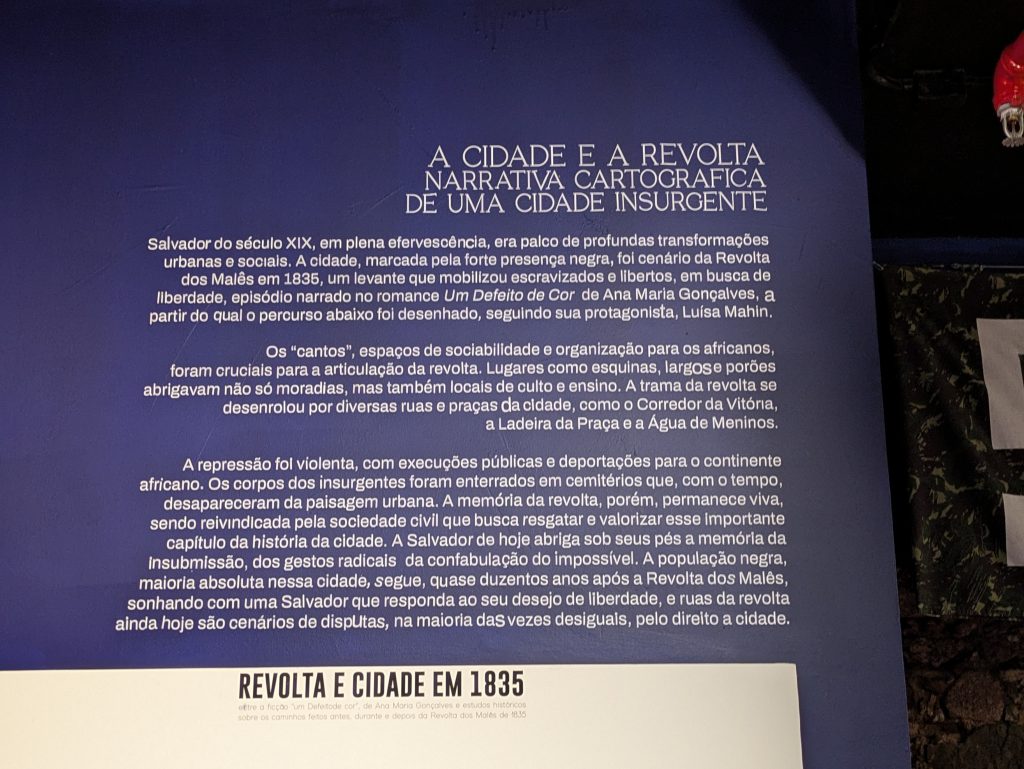

The top floor contained the exhibit about the Malê Revolt, a rebellion that was staged in Salvador in 1835, and was initiated, primarily, by muslims who were members of the Hausa ethnic group. In some ways, the exhibit was as much about the history of the revolt as it was a space for artists to reflect on the meaning and symbolism of the revolt itself. Historical events provide ways to examine key cultural themes and ideas, particularly those which are illuminated by the incident itself. To this end, there was a timeline of the revolt, along with other elements about its historical impact, (some of which were shared in other parts of the museum). However, most of the pieces were creative interpretations of Afro-Brazilian resistance and resilience.

There was also some brief discussion about the role of Islam during the revolt. This included references to the use of talismans containing Quranic verses, the use of Arabic script in the rebels’ communications, and so forth.

Overall, the exhibit was a good reminder of the intimate relationship between oppression and revolt–that the former almost always engenders the latter. Further, it demonstrated the ways in which African people sought to adapt their cultural knowledges to resist European domination. Lastly, it expressed the unfinished nature of this and many other struggles focused on the redemption of the African world.

Monumento Arena da Capoeira

As we were riding in an Uber the day before, we happened to notice a very large collection of sculptures situated around a large sphere representing Capoeira. Thus, after visiting the Mercado Modelo on Friday, we paid a visit to this space–which is just across from the market.

Completed in 2024, the Monumento Arena da Capoeira is a large spherical object encircled by statues of eight Capoeira masters: Mestre Besouro, Mestre Bimba, Mestre Caicara, Mestre Canjinquinha, Mestre Gato Preto, Mestre Noronha, Mestre Pastinha, and Mestre Waldemar. At its center is an elevated, circular platform featuring statues of two additional masters, Mestre Aberre and Mestre Totonho, playing Capoeira. It is a beautiful monument and a fitting homage to the legacy of these great teachers.